Without a college degree and with a résumé that featured more than a dozen years as a preschool teacher, Cheryl Volkman Knight, now 67, started AbleNet in 1985 in Minneapolis. Her time as a teacher supporting kids with cerebral palsy informed her decision to start the business. That job demonstrated to her the difficulties a person with disabilities encounters, developed her empathy, and ignited her interest in improving their lives.

At a conference, she saw a man showcase a switch — a device used to assist people with disabilities to help in their everyday activities. That device sparked Knight’s imagination, and she began to think of different ways that switches could help her preschoolers. Knight lacked the tools to make the switches until Lee Hallgren, an employee at Honeywell, came along. Hallgren saw a television program about switches, where someone was using their foot to tap buttons signalling “yes” and “no.” The device was very simple so Hallgren called United Cerebral Palsy to see if anyone within the organization had ideas for switches. United Cerebral Palsy made a call out for anyone who had ideas, and Knight responded, getting her in touch directly with Hallgren.

Co-founder and CEO of AbleNet Cheryl Volkman Knight enjoys cooking with her grandchildren. (Photo courtesy of Cheryl Volkman Knight)

Honeywell volunteers started making switches at night after work, and AbleNet became a reality. The nonprofit earned $20,000 in profit its first year, and five years later, AbleNet became a for-profit venture, earning close to $1 million in sales. AbleNet earned recognition in 1992, becoming a finalist in the social responsibility category for Minnesota in the Ernst & Young Entrepreneur of the Year Award. The globally recognized company continues to innovate and lead their field of assistive technology. Today, AbleNet is worth over $20 million.

Socially Driven spoke with Knight about the rewards of starting a business that seeks to assist a marginalized community, the difficulties in building a company that relies on technology, and the challenges of being a female CEO in a field dominated by men. Before 1995, female CEOs in any Fortune 500 company were a rarity, and even today, only 7.4% of those corner offices feature women. “[Cheryl] came from working with kids with disabilities and that always, always, guided the decisions she made. Always,” says Peggy Locke, former AbleNet director of education. “Some of the men that came into the company were more business-like, and that was always very difficult for her; going between the business side of it and the human side of it. That was very much a struggle.”

Knight is working on a book about her experiences. When she finishes, she aims to seek out a publishing deal. One potential is to publish through the Honeywell Foundation, where AbleNet was born. But here, she shares her journey from preschool teacher to a Fortune 500 CEO determined to help others.

This interview and the questions posed have been edited for clarity.

Socially Driven: How did your job as a preschool teacher inspire your interest in helping children with disabilities?

Cheryl Volkman Knight: I think I was passionate about people, period. I got to know the kids, I got to know the families. I was deeply connected to their pain and their joy, and boy, you help a kid learn how to hold a spoon to feed themselves; it’s really cool. Any time you immerse yourself in something, if it’s what you wanna do, I think you’re going to get passionate about it.

SD: What did you learn at the preschool that helped you launch AbleNet?

CVK: There was no technology. We had to do everything. We had to have a sock, put the sock on a kid’s hand and tape [a rattle] into it so that they could be part of the band. I think I got pretty good at trying to problem-solve. If you can define a problem, you can get the right answer. The other thing is that because I worked with kids with severe disabilities and their families and teachers in all kinds of settings for 13 years, I had a deep level of knowledge that gave me good instincts.

SD: How did AbleNet begin?

CVK: It was gradual in that we just kept following the opportunities, and we knew what we wanted. We knew what these products were doing for these kids and that just kept driving us. In the early days of our business, people didn’t believe that people with severe disabilities who we were serving could learn, could communicate. They just didn’t have a vision for their capabilities, and they didn’t have technology where they could prove what they knew. We had the opportunity to create the simplest products. We had a big vision. We thought, ‘The whole world needs this. Everyone with a severe disability needs this. We can be [a] part of that.’

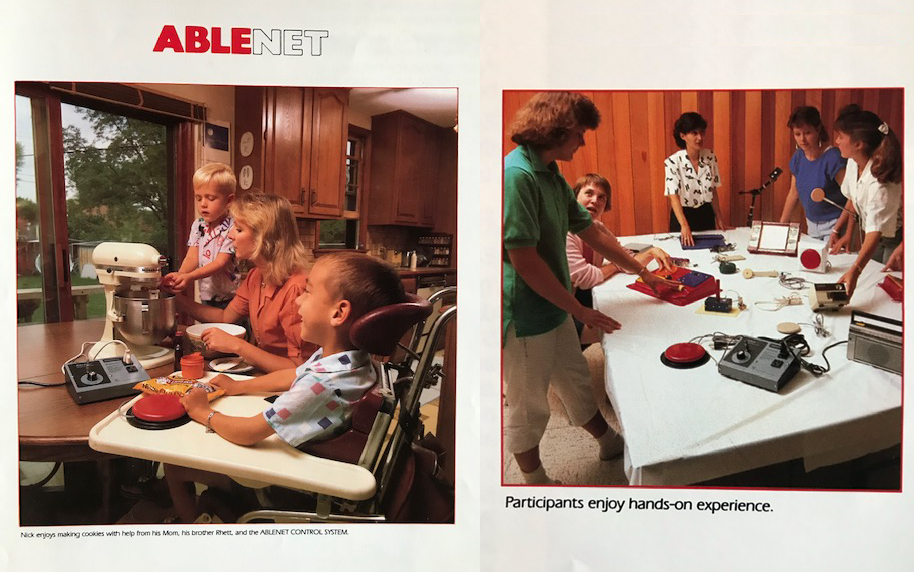

As this marketing material from the 1982 demonstrates, AbleNet technology has helped people with disabilities for decades. (Photo courtesy of Cheryl Volkman Knight)

SD: What does good leadership look like to you?

CVK: We need leaders who listen. We need leaders who don’t take the limelight, leaders who understand that they’re providing a service to their employees, not the other way around. I always told the stories monthly of kids with disabilities, and I would talk about having passion for our customers, and I had one guy who said, ‘I care about our customers or I wouldn’t have our job, but I care about quality and just because I don’t have passion for kids with disabilities or our customers doesn’t mean that I don’t have passion for quality and you don’t talk about that.’ I learned a lot from that, and I think that’s what leaders have to do: tell the truth and listen.

SD: How would you recommend filling the minority gap in leadership?

CVK: I think you gotta talk about it and know how to talk about it better than I did. I think all the stuff happening in Minneapolis, we thought things were better, we didn’t think it was a problem, but we’re not in the group that it’s a problem for. We weren’t asking the right questions to the right communities. So, that’s gotta change. And, there’s so much fear. I was afraid to work with people with cerebral palsy. I almost didn’t even go to that job interview. It was just ignorance and fear.

SD: So how did you overcome that fear?

CVK: I just started working. I fell in love with them. It was easy.

SD: What advice would you give to other social entrepreneurs?

CVK: I think the biggest advice is you got to be grounded in what you believe you’re shooting for. You’ve got to understand it, feel it, see it, know it, get so grounded, and have that vision so clear that no matter what comes at you, you can trust that your instincts will give you the right answer. If you’re so grounded in what you believe in and what you know, it’ll keep you going.

SD: What was it like being a female CEO?

CVK: I worked in nonprofits my whole life, and almost always, the executives of those organizations were men, not women. So, I didn’t have any women role models from an upper-management experience, which made it difficult. I asked for a female mentor because I was telling people how hard it was feeling confident in the decisions I was making with all these men. I thought, ‘Is there anybody I can talk to that would understand and help me navigate this from a personal perspective?’ I found a fantastic mentor. Her approach was always, ‘Tell me what you did and what you learned,’ and because I was focused on what I was learning, I was not focusing on any failure. It kept me out of a chaotic mindset because I didn’t focus on punishing myself or doubting myself.

SD: Did mentorship become a fixture of your career?

CVK: We mentored a ton of companies that were just starting their ESOP (Employee Stock Ownership Plan) programs. We shared our policies, we did our public speaking, I wrote articles, I was on the state board, and I was president of the association in Minnesota for a while. So, I met with all these people at the national organization and we mentored a lot of them. I was never an official mentor because I was involved in so many organizations and with so many people. It was always kind of cold-mentoring, sharing ideas, sharing policies.

SD: Do you still feel like you’re being mentored now in any way?

CVK: One of the women who I worked with has mentored me on the book for about 10 years. She really helped me get started, and then she moved from that mentorship into being an editor for the first draft. Her big thing was, ‘Just do it, you’ll figure it out.’

SD: Tell me about the book.

CVK: It’s a great story about connecting. It’s a story about how you can make a difference. I think the timing right now is really interesting because look at what is happening to the world with COVID — people are doing some amazing things. They’re figuring things out, they’re coming up with solutions. The world won’t be the same because of some of the things that they are coming up with. It’s a beautiful story. I’m trying to let go of the outcome that might happen and who it might help, but I’m filling in a lot of detail that I think any entrepreneur could use.

SD: Do you enjoy writing it?

CVK: Some of my friends who know I’ve been struggling and working on this for 10 years say, ‘Well, why are you writing this if there’s so much pain involved?’ Hard is not a bad thing. You learn a lot. So my answer is always, ‘Because it’s a great story. It needs to be told. What people did, what Honeywell did, how kids changed, what parents did. It has to be told.’ So, I have to do it.

SD: What has your career taught you?

CVK: I think for me, I keep learning that I need to ask questions and listen better. Everytime I thought I had an answer at AbleNet, I would learn that’s only part of the picture. Maybe that’s the biggest life lesson — you gotta ask for help. One of my greatest downfalls was not having an education or thinking that I didn’t know what I needed in order to do the job. But the greatest gift is that I didn’t because then I had to ask for help from all these incredible advisors.

SD: If you had the opportunity to start this all over again, is there anything that you would change in the process?

CVK: I think, for me, if I could change anything, I would change my beliefs in my own confidence. My fear of being a bad leader, of mucking up the business, led me to make a few mistakes. That’s the only thing I could really control. I think one of my greatest challenges was my lack of confidence, but one of my greatest gifts was my lack of confidence because I knew I needed help. I knew I needed assistance from people that had been doing pieces of building a business successfully long before me. And, I listened to them. And, they loved sharing. It’s a beautiful thing when you really allow people to be involved. You really trust that they’re giving you their best advice.